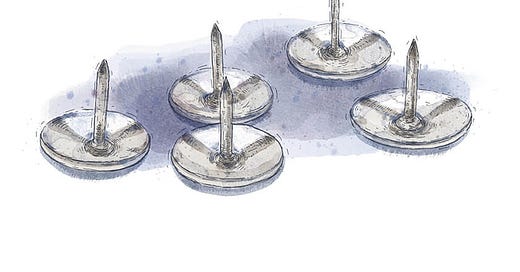

Thumbtacks

On a Friday at the beginning of December, one of us found a box of thumbtacks on the bookshelf under the cork board where weekly assignments were posted.

On the first day of seventh grade, I arrived in a cloud of gray diesel smoke. Our school was small and owned only one old yellow bus for all the grades. The youngest kids gingerly walked down the steps of the long, trembling GMC and out the wide-open accordion doors while the older kids impatiently followed.

The seventh and eighth grades shared one spacious room in the front corner of the building. To the left of the door, on white paper taped to the wall, someone had written “GRADES SEVEN AND EIGHT“ with a bold, blue marker. Under the heavy block lettering was scrawled, “Welcome.”

We trickled into the room, finally pooling in the desks around the windows. The yellow September light filled the square room with gold, and the open windows let the fresh breezes blow lazily over the desks.

I was looking out the window and listening to the low rumble of the bus pulling away from the front curb when the room became suspiciously still. Our new teacher, Mr. Fowler, had walked through the doorway, taken a halting step into the room, and stood eyeing us. He swept the scene left and right without a word. “I have seating assignments,” he said. We all looked at him. “So,“ he began but paused. We waited quietly and watched him. “Everyone stand in front of the chalkboard while I call the roll and tell you where to sit,“ he said in a voice grim with authority.

After we were seated, class began with a litany of rules and the consequences for infractions. With the passionless drone of an IRS bureaucrat, Mr. Fowler articulated each point of his code of conduct until, with a halting breath, directed us to open our history books. Within an hour on the first day of school, I longed for the last period with the hope of a criminal awaiting his parole.

It is doubtful if anyone could have bonded with a class of mostly seventh and eighth-grade boys, but Mr. Fowler had grown old beyond the reach of adolescence. He was sullen and taciturn. We liked him less each day, and he returned our contempt with a callous sternness. Any good graces we may have cultivated in the first months of school were withered. But we were surprised at a teacher’s cold grudge that chilled the classroom as the biting fall air began to frost the old window panes.

On a Friday at the beginning of December, one of us found a box of thumbtacks on the bookshelf under the cork board where weekly assignments were posted. We took advantage of Mr. Fowler’s sloppiness. A few of us grabbed a tack and patiently waited.

Later in the afternoon, he assigned us reading and quietly left the room. He would not be gone long. Five separate boys, each gifted with one silver tack, quickly walked to his chair and laid theirs on the soft black cushion. Then, we waited. Mr. Fowler returned, walked to his desk, and sat down. In the absolute silence, we held our breath. But there was no shriek, and he sat stoically grading our assignments for the next 15 minutes. Our confusion drifted into dejection. Then, Mr. Fowler pushed back his chair, stood, and walked to the blackboard.

In the back of his black pants, five silver tacks gleamed in the clear December sunshine that slanted through the eastward-facing windows. Every boy held back their laughter with a courageous resolve that lessened with each stroke of Mr. Fowler‘s chalk.

As our teacher wrote over the dusty gray board with a vigorous hand, we watched the tacks shake in the seam of his pants and bounce with the purposeful crossing of each letter t.

In large capitals, he wrote the word IMPEACHMENT. Each letter threatened to jostle the tacks from their hiding place. He turned to look at the class as a precaution. But we were transfixed by the tacks. The room was preternaturally quiet.

With a flourish underlining the name he had written—Andrew Johnson—the first tack sprang loose from his backside. A hissing snicker sizzled from most of the class. Mr. Fowler turned on us with a quick, striking look. His tie, weighted with a silver clasp, sluggishly followed, moving like a pendulum. I lowered my head and straightened the looseleaf notebook paper spread on the top of my desk. I breathed shallow puffs and waited to hear the click of chalk on the blackboard before I looked up.

Another tack dangled from his pants and dropped as he wrote Richard Nixon, then like a heavy drop of rain dripping from a wide sycamore leaf on a wet spring day, another tack fell, sounding a hollow plink when it hit the industrial carpet that lined the classroom.

One tack clung desperately to the seat of Mr. Fowler’s pants. With great energy, our teacher added the disgraced Marylander Spiro T. Agnew’s name to the chalkboard as the final tack shook loose. In one collective guffaw, both boys and girls exploded under the pressure of restraint.

Mr. Fowler spun toward us again and stoically stood as everyone laughed without pretense. My sides ached, and my throat scratched with dryness.

The new year began under an icy cloud of anxiety. We shuffled back through the faded doors of the school and into the hallway heaving with elementary grade children.

Our teacher was looking around the room when the glint of the five tacks arrested his investigation. He slowly bent over, and, with one hand, picked them up. He held the tacks in his open palm, studying them as his whirring mind made sense of the tacks, the laughter, and his place in the center of the joke.

Without comment, he stomped to the classroom door that was propped open and closed it with a sharp slam. He walked to the chalkboard, wrote the title of our history book and page numbers, and then, with a shaking hand, wrote READ in large block letters. We did.

Questions about the assignments, even requests for the bathroom, were ignored with an icy silence. Soon, we excused ourselves. Though we watched for any expression from Mr. Fowler out of the corner of our eyes, none came. The coldness of our teacher grew with the coldness of the days as we neared Christmas.

For two weeks, our teacher was silent and automatic. Our only assignments were reading textbooks. There were no quizzes, no tests, and we were delighted but anxious.

By the day before Christmas Eve, Mr. Fowler had not spoken to the class in over two weeks. We had read the textbook that contained the year’s history curriculum and were saturated in English literature and earth science. Reading a math textbook is drudgery; without quizzes, we had no assurance that the problems we solved were correct.

At the end of the school day, we dismissed with a perfunctory message on the blackboard. “Go,” it read. We left school to begin the long Christmas break and, other than a wry smirk, thought nothing about our teacher's reticence.

The new year began under an icy cloud of anxiety. We shuffled back through the faded doors of the school and into the hallway heaving with elementary grade children. We fumbled our bags off our shoulders and stuffed them under our desks. Our coats were hung on large brass hooks to the left of the classroom door.

The radiators hammered, and a metallic echo bounced around the classroom when the principal walked in with another woman. It was Miss Longstreet. She was a frequent substitute with a reputation for educational vigor and a wandering eye that let her watch both sides of the classroom simultaneously. No one misbehaved because she saw everything.

Our principal sighed in exasperation. “Mr. Fowler will not be back. He has resigned. According to him, this class is incorrigible and hopelessly beyond the help of any teacher cursed to stand before you,” she said. We were suspicious and unsure what incorrigible meant. “Miss Longstreet will be your teacher for the remainder of the year,” he ended. We all looked around furtively.

Our class had drawn the black spot. We were marked with an indelible shadow. The younger children moved out of our way in the halls, and the high school boys looked at us with reluctant respect.

The school week went by slowly with the dreary cadence of quizzes and discussions. We heard rumblings from our parents that a group of school board members were meeting with Mr. Fowler to consider his grievances and restore him to the position from which he recently vacated.

For months, the boys in the class had made groveling arguments that Mr. Fowler was a tyrant. We were all told to obey the teacher. Open your ears, not your mouths, our parents said unanimously. When we pleaded that he was crazy, they would say teaching seventh and eighth-grade boys would make anyone crazy.

But after the school board meeting with Mr. Fowler, my friend’s father came home with a fresh understanding and a reluctant repentance that we learned of the next day.

When he came into the house, he closed the door pensively. My friend’s mother asked what was wrong. There was a distant look in his eyes. Tiny beads of sweat glistened on his upper lip. He shook his head, chewed his lip, and cleared his throat twice.

He pointed a shaking hand and considered his language carefully. Then, convinced his words were correct, succinctly said, "You boys were right. He is crazy.”